Defining Administrative Law

Administrative law is a body of law that governs the activities of administrative agencies of government. It is the branch of law that deals with the actions and operations of government agencies, in particular those that regulate government administrative operations. Given the large number of specialized government agencies, each with its own set of rules and procedures, however, locating a single definition for administrative law would be difficult.

Most of what administrative law is concerned with concerns the executive branch of government, as this is the branch of government with the power to establish and oversee the numerous government agencies that employ administrative law . It involves both the rulemaking process as well as enforcement of those rules, adjudication of regulatory agendas, and enforcement of limitations on the powers of those agencies. Administrative law can also be seen as the area of law that constrains the executive branch of government in carrying out its duties.

Part of the reason that administrative law is so vast is that administrative agencies exercise a large degree of discretion in their rulings, prosecutions and rule-making. Therefore, there must be a large body of law dedicated to keeping that exercise of discretion within legal boundaries, giving citizens the chance to appeal unfair or unreasonable executive action.

Instances of Administrative Agencies

Administrative agencies can exist at the federal, state, and local levels – though only federal and some state agencies have broad-based regulatory authority. Administrative agencies are regulatory bodies that have authority to issue rules, adjudicate disputes, and enforce laws within their areas of oversight. Congress creates federal administrative agencies, while state legislatures create state administrative agencies. The delegations of authority from Congress and the state legislature are granted pursuant to enabling statutes that prescribe the powers the legislative body wants to delegate.

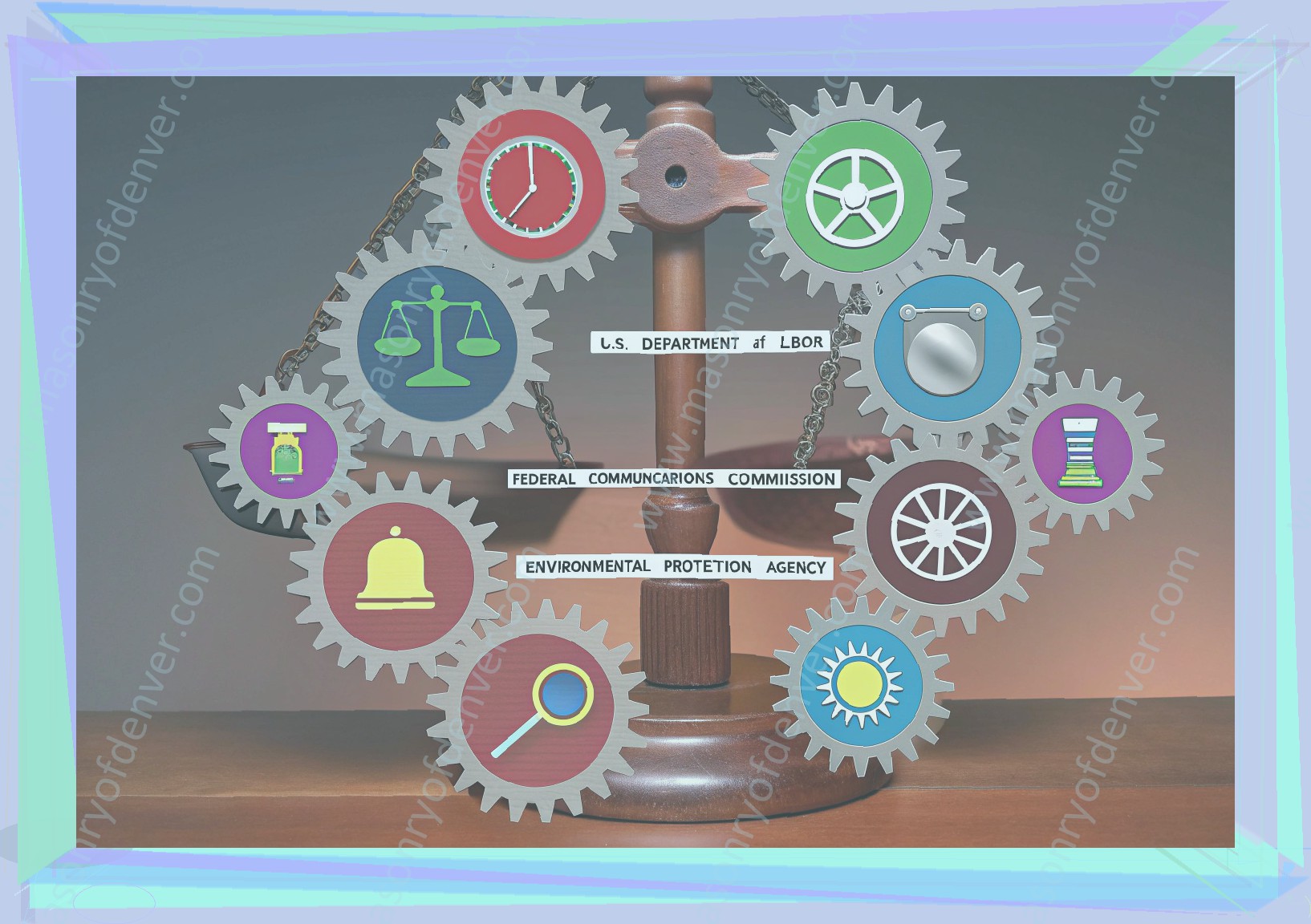

At the federal level, agencies typically have jurisdiction over both state and national boundaries, which are known as "federal agencies." Administrative agencies that exist at the state level are created pursuant to each state’s constitution and statutes. State agencies usually only operate within the state’s boundaries. The following are just a few specific examples of administrative agencies: U.S. Department of Labor, Federal Communications Commission, Securities and Exchange Commission, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Food and Drug Administration, Department of Energy, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Education, and National Labor Relations Board.

The Process of Rulemaking Defined

Administrative agencies engage in what is known as rulemaking, the act of promulgating rules or creating regulations, typically through exercise of a grant of power from Congress. There are two main mechanisms by which agencies can do this: formal rulemaking and informal rulemaking. A general understanding of these alternative procedural requirements is necessary to fully grasp how administrative bodies create rules.

Formal rulemaking occurs through a process established by the Administrative Procedure Act (the "APA"), 5 U.S.C. § 551 et seq., whereby formal trial-like hearings are held prior to the promulgation of the rule. Formal rulemaking involves "on the record" rather than "on the basis of the record," as required for formal rulemaking, and therefore can be distinguished from "formal rulemaking."

Informal rulemaking is considered "on the record," but not "on the basis of the record." In informal rulemaking, the agency will typically file a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register, soliciting public comments. The agency will then consider all relevant information provided and publish a Notice of Final Rulemaking, usually in the form of final administrative regulations in the Code of Federal Regulations. This process is the most common mechanism used by administrative agencies to promulgate rules.

The APA requires federal agencies to provide the public with notice of proposed rulemaking and allow interested persons the opportunity to submit written data, views, or arguments with respect to the proposed rule. The APA, however, allows agencies to adopt rules without the formalities of notice and comment when the rules are interpretive, as opposed to legislative. Legislative rules have a substantive effect that is dispositive, whereas interpretive rules are meant to provide guidance for the general public and are not legally dispositive. Informal rulemaking is not required if the agency for good cause finds that notice and public procedure are impracticable, unnecessary or contrary to the public interest, such as in the case of "emergency" rulemaking.

In addition to notice-and-comment, federal agencies will commonly enter into negotiated rulemaking to obtain the opinion and suggestions of the public. Negotiated rulemaking is an effort by agencies to simplify the procedural aspect of rulemaking and allow the public to create proposed legislation. The agency publishes a Notice of Negotiated Rulemaking, appoints a representative, holds hearings and consultations and then formulates the proposed rule based on the results of the negotiation.

At the state level, agencies also engage in rulemaking, sometimes codified in law under Ohio generally as informal rulemaking, ORC § 119.03 et seq., as discussed below. State administrative agencies are typically not obligated to follow the same rulemaking procedures as federal agencies, although federal and state statutory law may require similar procedures.

Administrative Law Adjudicating

Administrative adjudication involves the actions and decisions taken by a government authority to implement the law and policies under that governmental authority’s jurisdiction. The health and safety, labor, and housing departments are just a few of the many governmental authorities authorized to pass administrative laws.

To explain further, Section 551.002 (5) of the Texas Government Code defines an "agency" broadly as, "[a] state or regional governmental or quasi-governmental subdivision, including a board, commission, department, office, council, or institution of this state, having statewide jurisdiction, whether within or outside the executive or judicial branch of state government, and whether composed of one or more persons."

All state of Texas departments fall under this definition. Local government authorities, such as counties or municipalities, do not always fall under this definition, though. For example, the Williamson County Sheriff’s Department may not be considered an agency and many subdivisions of the government do not pass administrative laws.

Although an "agency" is broadly defined, it is not always a large, unwieldy government body that has existed for an extensive period of time. To the contrary, many agencies come and go or are redefined because of the short-lived nature of many governmental organizations.

Agencies within the state of Texas can initiate a contested case by petitioning itself. For example, if the Texas Department of Transportation needs to implement a new state road project, its would petition itself to create a new process for acquiring right-of-way. In this case, the Texas Department of Transportation would petition itself to initiate an administrative process to resolve any disputes arising under this new administrative law.

When a petition is filed to initiate an administrative adjudication, the agency is then required to make a determination. It is at this stage that the administrative proceedings can end, subject to judicial review, or proceed into a contested case.

For example, imagine a 50-unit apartment complex is being built on vacant property in a Texas suburb. Once the property is made available to the general public, a few neighboring property owners realize that the land has a drain ditch and culvert that runs directly across the land. These property owners file a construction permit protest with the subdivision authority.

After reviewing the protest, the subdivision authority issues a decision regarding the protest. Primarily, the subdivision authority concludes that the construction permit application should not be approved and no construction should be allowed over the drain ditch and culvert. The subdivision authority informs the property owners of its decision and provides any necessary citations of law in support of its determination. The property owners are satisfied and the contested case ends. The subdivision authority will, however, keep its decision for future reference regarding similar property disputes.

In the above example, the property owners could have satisfied their goal without initiating any sort of administrative adjudication. However, in real life, property owners do not get exactly what they want merely because they ask nicely. For this reason, property owners usually choose to initiate an administrative adjudication to resolve a dispute with a governmental authority.

Continuing the above example, assume that instead of being satisfied with its decision, the subdivision authority instead denied the property owners’ request and informed them that it will allow other property owners to build above the drain ditch and culvert.

At this point, the property owners in this example have two choices. First, the property owners could file suit in district court to initiate a de nova proceeding asking the court to resolve the dispute and determine an outcome. Alternatively, the property owners could initiate the contested case and move forward through the administrative process. Typically, the latter approach is preferred but certainly each situation is unique and ought to be analyzed separately.

It is important to note that local government entities, such as municipalities or counties, are not required to conduct contested cases like state agencies. Alternatively, the local governmental entity can choose to terminate the contested case when it becomes burdensome.

The parameters of administrative adjudications vary significantly so every situation should be carefully analyzed and all possible complaints addressed.

Judicial Scrutiny of Administrative Activities

Judicial review of administrative decisions provides a critical check on agency power by holding agencies accountable for their decisions when they are outside the bounds of the law. Utah Animal Rights Coalition v. Salt Lake County/West Valley City Health Dept., 130 P.3d 301,303 (Utah 2006). Under the Utah Administrative Procedures Act (UAPA), U.C.A. § 63G-4-401 et seq., any person that has "substantially affected" interests, can seek "judicial review of government action." Id. Any "person adversely affected or aggrieved by agency action" may obtain judicial review of agency action if, among other things, that action exploits a statutory method of review and the agency action constitutes an order or ruling that must be first be appealed to another agency before petitioning the court under § 63G-4-403(2)(c). Id. Under the UAPA’s "any person" standard, applicants and neighboring landowners have been able to file a petition for judicial review. Id. For example, in Utah Animal Rights Coalition , a non-profit animal rights advocacy group brought a petition against West Valley City, the city that issued a license to animal shelter Best Friends, arguing that animals shelters should not be located in heavy industrial zones and that the license was more regulating an illegal dog kennel rather than an animal shelter. Id. at 302. Best Friends responded with an affidavit from the manager who stated the shelter’s four objectives was to provide emergency rescue for stray animals, provide shelter, spay or neuter the animals, and devise plans to place the animals in loving homes. Id. The trial court granted summary judgment to West Valley City. Id. at 303. The Utah Supreme Court upheld West Valley City’s approval of the license to Best Friends stating, "The first and foremost purpose of an animal shelter is to rescue and shelter animals…To suggest that dead K-9s in our jails might be in need of community shelter tells us that the K-9 needs our help and we have a moral duty to intervene." Id. (citing Southfield Police Chief v. City of Southfield, 702 N.W. 2d 658, 662 (Mich. App. 2005).

Notable Precedents in Administrative Law

Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984): This seminal case established the doctrine of "Chevron deference," which holds that courts must accept as conclusive an agency’s interpretation of a statute that it administers, unless the interpretation is unreasonable. The Court found that Congress had given the EPA the power to make rules to implement the Clean Air Act, and that the agency’s interpretation of the statute was reasonable.

Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, 549 U.S. 497 (2007): In this case, the Supreme Court held that the EPA has the authority to regulate greenhouse gases. The Court determined that the Clean Air Act gave the agency the discretion to determine if such regulation was necessary, and found that the EPA could not avoid regulating greenhouse gases solely because it would be difficult to do so.

Judicial Watch v. U.S. Department of the Commerce, 466 F.3d 405 (D.C. Cir. 2006): The court held that an agency is not required to justify its investigatory preferences in using statutes in a particular manner. The court distinguished between the lack of statutory authority and an abuse of discretionary power. The court also held that the plaintiff did not have standing to challenge the agency’s policy because such a case or controversy did not exist.

Circle C Investments, LLC v. Land Use Commission, 2012 Conn. App. LEXIS 162 (Conn. App. Ct. July 31, 2012): The court held that an agency’s decision to approve a controversial large-scale site plan application is not a final decision subject to appeal. The agency’s decision was not final because it was not subject to appeal under General Statutes § 8-8 and therefore the Court held that it did not have jurisdiction.

Administrative Law Troubles

In its many forms Administrative Law faces significant and complex challenges. Granting administrative agencies rule-making and adjudicatory power raises concerns over their broad and arguably unchecked authority. While agencies are constrained by the laws that enable them, the enormous legislative power they possess remains a frequent target of criticism. This criticism is aimed at the weak checks imposed by the Legislative and Executive branches of Government and the potential for agencies to over-reach the boundaries created for them by the enabling legislation. These, however, are not the only administrative law challenges. Administrative Law faces ever-looming issues concerning its transparency and accountability.

Despite appearing to be narrow, enabling legislation often grants immense authority to agencies. Under some organic acts, specific agency action is not even required; rather the agency merely must undertake the proper process, whether rulemaking or adjudication, before enacting a regulation or taking some other action. As such, agencies wield enormous power to shape the laws under which they operate.

Further, unlike other areas of law, the availability of judicial review to remonstrate agency over-reach and refusal to follow the law is limited. Judicial review of agency activity may happen as of right. However, legislative efforts to make judicial review the sole remedy have become law in one instance at least. In that case, Meyer v. McAninch, a trial court held that the action of the Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration State Trust Land Management Act within a special zone set aside for a U.S. Air Force fighter base did not require Utah’s State Institutional Trust Lands Management Act (SITLA) review procedure. The Act directs that any action of the Trustee is "subject to judicial review upon passage prior to December 31 , 2002." This effectively creates a "lock in" without relief until the next session.

The lack of stringent review measures and checks on agency power is somewhat lessened by the trend toward profiling and defining agency power by means of informal collective procedural rules and guidelines issued by the Office of Administrative Hearings, and made available through public agencies. This practice maintains some accountability over the actions taken by an agency and limits the abuses of power by requiring the agency to act within its powers as delineated in its administrative procedure rules and guidelines.

Another contemporary challenge comes from the public’s response to agency action. The recent campaign against the rules implemented under the Department of Labor’s "Persuader Rule" serve as one example of public disapproval with agency action. When a lobbying group convinced U.S. District Court Judge Sam R. Cummings to block the Department of Labor from enforcing the Rule pending the outcome of the group’s lawsuit, the measure immediately caught the attention of media outlets and public interest groups. A recent survey by the Chamber of Commerce revealed that 90% of Americans believe that the Rule will prevent employees from seeking adequate legal counsel; 87% believe the Rule will restrict employee access to important objective information regarding labor organizations involved in collective bargaining. In the face of imminent backlash to the Rule, the Department of Labor withdrew it, though without admitting fault. The President also provided a mandate to repeal outdated agency rules, and agencies across the country are acting upon it.

The effects of citizen reaction are felt by the legislature’s as they watch their priorities being re-funneled through citizen opposition to perceived abuse of administrative authority.